William "Henry" Huntington (1820-1885): Paris Correspondent and Antiquities Collector

- Maggie Meahl

- Feb 19, 2025

- 5 min read

I thought I was going to NYC this week to look at C. P. and Maria Perit Huntington's youngest son's important collection of Founding Father memorabilia at The Met, however, a Penske truck with ice on its flat roof had others ideas. Not hurt but windshield was.

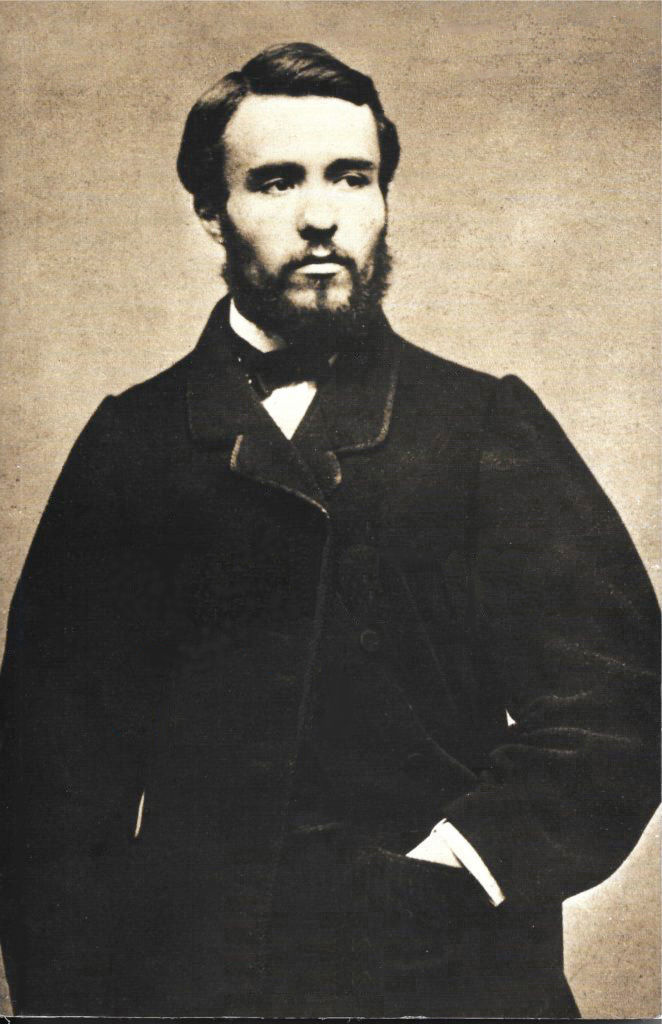

William "Henry" Huntington (1820-1885) was the youngest son of C.P. and Maria Perit Huntington (see my previous blog posts). Named for the popular "Log Cabin" general (and Whig), Henry rejected a mercantile career early on (just like B.F.). He eventually carved out an interesting life for himself in Paris, from the 1850s to his death in 1885. Upon his parents' death in the 1850s, Henry inherited quite a bit of wealth in stocks and probably some land.

Little "Henry," baby of the family of nine that lived on Washington Street, started off life going to a "dame school" followed by Miss Goodale's hipped-roof East District schoolhouse in Norwichtown. It was during these early years, he became friends with a minister's son: Donald Grant Mitchell (1822-1908).

A bright young man, in the late 1830s, Henry was fitted for college. First, he tried the new Wesleyan, the first Methodist college in the United States (Middletown, CT). Henry was homesick and father C.P. seemed to miss his youngest son too--especially as family dynamics were changing. Two letters survive at the William L. Clements Library at the University of MI (Ann Arbor) that document their relationship at this time. Incidentely, their handwriting was very similar.

Two years into Wesleyan Henry left and transferred to Harvard in August 1841. After that, I think I remember reading that he lived in Boston for a while perhaps as a druggist.

Like most in his family he was described as being tall, with dark brown hair, fair skin, and brown eyes. These descriptions can be found in U.S. passport records accessed via Ancestry.

By the late 1840s, he offered to write a short bio on his friend: Donald G. Mitchell (1822-1908) who had just published his breakout book: The Reveries of a Bachelor in 1850 and was famous. Henry served as his old friend's sometime book agent and soulmate.

Whether or not they had an amorous relationship, we will never know. When he could, Henry visited Don at Edgewood, his gentleman's farm, in New Haven. Both were creative types. Don had a young family but suffered frequently from bouts of depression. Henry always tried to cheer him up.

Anyway, between, say 1841-1855, Henry probably bounced from the Cambridge/Boston area to Norwich, New York City--and France. By 1857, he had permanently moved to Europe according to his passport records. During this time period Henry was setting the seeds for a notable writing career, based in Paris, as a correspondent for Horace Greeley's anti-slavery newspaper: The New York Tribune.

Henry was part of a group of prominent American expats in Paris who were feverently anti-slavery. Never married, he did not have responsiblity as a husband and father. He supported himself through writing, being an agent, and probably on inherited money nurtured via Yankee frugality.

Henry lived in Paris during the early part of the Third Empire (1870-1940). A very volatile period, he was able to report on things like the Siege of Paris (1870-1871) when the Germans starved the Parisians. Henry reportedly quietly donated funds, during the Siege, to the mayor of Montmartre: Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) who was forever grateful. Henry lived in Montmartre on the Rue de la Bruyere. He had a maid named Angele.

Henry was a likeable sort. Like most creative types, he smoked, drank, and turned every sentence into a lesson on humorous figurative language: "rummest bronze medallion," "Pactolian draughts," "Franklinieacs," "handsome not pretty," "smashers" for inkblots," and "Prince Napkin" for Napoleaon III. The list goes on. Very Mark Twainesque.

He was described by a Mitchell biographer as "happy and wholesome" and living the life as a "recluse" bachelor in Paris--not so sure about that--maybe the last few years. During these last few years, he was painted at least two times.

Henry's "salon" group evolved over time and included diplomats, artists, musicians, writers, and more. One couple of the group was Robert Ogden Doremus and his presumably wealthy wife, Estelle Emma Skidmore Doremus (1830-1905). Others included: Walter Gay, Caroline Cranch, and John Bigelow.

Henry and Bigelow each, were intense collectors of Founding Father art and papers, including Franklin's re-discovered autobiography that Henry helped Bigelow purchase (as an agent) in January 1867 from a French aristocrat. Another close friend, Bigelow referred to Henry as his "cherished friend."

Using a cane and an umbrella, and a cab, Henry physically carried off the DuPlessis pastel of Franklin for Bigelow, took it to a "print seller" and had it packed to be sent to Bigelow in London. Bigelow paid 25,000 Francs for the famous pastel. It was an exhausting day. It was gifted to the NYPL at Bigelow's death.

To put the money into perspective, Henry charged his friend 21.50 Francs for the packing and shipping the iconic piece of art to London.

Henry's own collection of Early Americana, amassed over decades, was donated to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York, right after his death, in 1885 at the age of 65. This collection is on view behind the glass cases at The Met in section 774 (I think).

Henry also left $50,000 to The Met. His only remaining kin were B.F. and numerous nieces and nephews. I don't think he left anything to them.

B.F.'s second son, Joseph, named his second son William Henry Huntington, in 1883.

Good friend Estelle Doremus kindly cared for Henry on his Parisian deathbed. His body was shipped back to Connecticut and buried in Yantic cemetery, across the street from where he grew up.

Selected Main Sources:

Bigelow, John. Some Recollections of the Late Edourd LaBoulaye, New York: G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1889.

Dunn, Waldo H. The Life of Donald G. Mitchell, New York: Scribner and Sons, 1922.

Howe, Winifred E. A History of the Met, Vols. I and II, New York: Columbia University Press, 1913.

Comments